Thoughts

Events for Old Time Love Songs

There are two events for Andrew Schelling's translation of Old Time Love Songs in February. On February 14th, the translator will be reading at Tor House in Carmel, California; there doesn't look to be information about it online yet, but you might check their website. Then on February 17th, he'll be reading with Red Pine at Seattle University; details are here.

Rest in peace Vinod Kumar Shukla

It is with regret that we note that Vinod Kumar Shukla passed away on December 23rd, 2025, at the age of 88; he was given a state funeral with honors on the 24th. There’s been a great deal of press:

- The Hindustan Times, and a second piece there

- The Federal, and a second piece there

- Scroll.in

- The Indian Express (with one of Arvind’s translations); and another piece there that mentions Treasurer of Piggy Banks

- The Times of India

- The Hindu

- The Economic Times

Scroll.in has excerpts from his fiction and a poem that Arvind Krishna Mehrotra translated for us. Achal Mishra’s documentary about the poet, Char Phool Aur Hain Duniya Mein is also up on YouTube in full at the moment.

Interview with Andrew Schelling

Paul Nelson has posted a forty-minute interview with Andrew Schelling about his Vidyā translation, along with a short excerpt from Old Time Love Song Magic.

Events for Old Time Love Song Magic

Translator Andrew Schelling will be at an event for Old Time Love Song Magic at Tor House in Carmel, CA, on February 14, 2026. More information as it becomes available.

Events for #evolutionarypoems

There are events for #evolutionarypoems! Here's what we have so far:

- Austin, Alienated Majesty, Tuesday, November 25, 2025, more info here.

- Washington DC: Lost City Books, Thursday, December 4, 2025

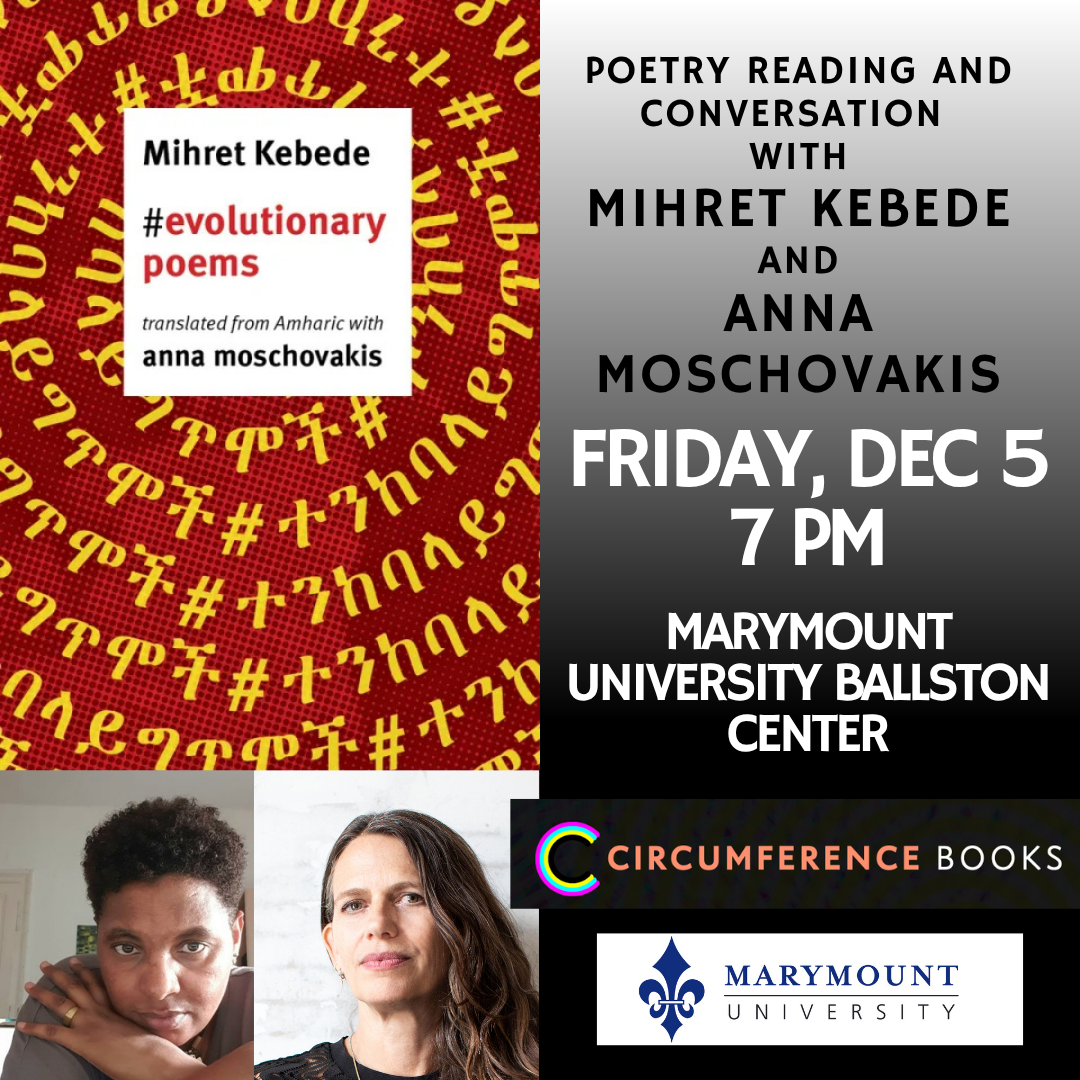

- Arlington, VA: Marymount Ballston Center, December 5, 2025, 7 p.m.

Here’s a flyer for the Marymount University event:

Vinod Kumar Shukla wins Jnanpith Award

More Vinod Kumar Shukla news: he’s won the Jnanpith Award, one of India’s most prestigious awards. The official site for the award doesn’t seem to have been updated yet, though it’s in a bunch of news stories out of India.

(Also! Literary Activism has put out an Indian edition of Treasurer of Piggy Banks. You can go there and read translator Arvind Krishna Mehrotra's introduction to Treasurer of Piggy Banks, as well as another piece he wrote about the poet.)

Woodland Pattern’s Small-Press Bundle

If you sign up for Woodland Pattern’s Small-Press Bundle this month, you’ll get a Circumference book! It’s Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s translation of Vinod Kumar Shukla’s wonderful Treasurer of Piggy Banks. Even if you already have a copy – I hope you’re up to date on our catalogue! – subscribe anyway, give our book to a friend, you’ll still get a new book by Renee Gladman (!) and Jimin Seo’s debut collection.

Documentary about Vinod Kumar Shukla

MUBI in India (and maybe in other places) is showing a documentary on Vinod Kumar Shukla, Achal Mishra’s Chaar Phool Hain Aur Duniya Hai. Some of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s translation of Treasurer of Piggy Banks feature in the subtitles! Though there’s no credit, which is a disappointment. But watch it if you can – there’s some discussion of it on Letterboxd as well.

Online Reading for A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder

On Saturday, 22 February, Poets House is presenting an online reading by Brynja Hjálmsdóttir and Rachel Britton presenting A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder. Tickets are free! More information here.

A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder in New York

Poet Brynja Hjálmsdóttir and translator Rachel Britton will be discussing A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder at Scandinavia House in New York on 9 January 2025 at 7 p.m. Details here.